Our Nervous Systems are Working Overtime to Keep Us Safe in the Midst of Uncertainty

There is so much being written, said, and spread about Coronavirus, COVID-19, and life in quarantine presently. I’ve withheld myself from adding to the noise.

Here’s the thing though: there is a LOT of contradictory information out there. Contradictions said between people in authority and between people speaking from their expertise. It’s confusing.

Our bodies interpret these contradictions as chaos. The chaos translates as a threat to our survival. Our amygdalas (as seen as the thumb in the picture below) are the alarm bell system of the brain. They are all presently hyper-alert, screaming “Give me back my independence,” Give me back my freedoms,” “Give me back my financial security,” “Give me back my sense of immortality,” and “Give me back my connection with others.” It’s a lot of loss, a lot of grief we don’t like and don’t want.

All of this protest, whether fight-or-flight energy, has gotten locked within us. Fight can be either a physical or verbal attempt of overcoming danger and flight is our attempt of getting away from danger. Picture Usain Bolt caught and restrained mid-flight. Picture Jackie Chan getting his arms and legs tied to his body mid-fight. Picture Martin Luther King Jr. presenting his “I have a dream” speech, and mid-sentence, his lips are glued shut and he’s unable to speak.

All that fight-flight energy pushed back inside the body without a way out throws the nervous system off balance.

Science has shown that the lasting impact of difficult events on the brain and body is related to how we make sense of the event and our experience rather than the event itself. Consider how two people may both be told at a ticket office for a new movie “Sorry, we’re all sold out.” One person might say “Bummer, well, can I have a ticket for the next movie then please?” While the other person may seemingly overreact with, “This always happens to me. I came 20 minutes early! Is this for real? There has to be some way!” Both people were told the exact same thing. Their reactions to the event are quite different. The first person maintained Upstairs Brain capabilities, while the second person slid down quickly into Downstairs Brain reactivity.

Similarly, some people in quarantine are having a very difficult time, while others are able to utilize the time to accomplish projects around the house and complete To-Do List items that have been on hold in the busy day-to-day life pre-quarantine. Personality type (ex. Introversion vs. extroversion), trauma history of unfortunate incidents, general felt-sense with structure vs. unpredictability, the safety of the quarantine environment, and the familiarity and likability of the people in the quarantine environment are only a handful of variables that allow each person’s experience within the collective experience to be unique to them.

Anxiety is one of the most contagious emotions.

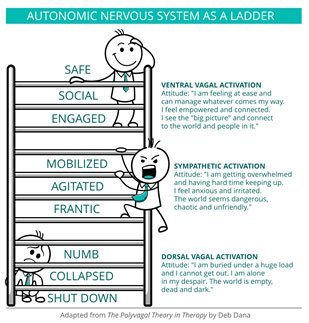

The picture named “Figure 2.1” identifies what happens in our bodies when we move from our Parasympathetic Nervous System—our rest and digest or tend and befriend state—into a Sympathetic Nervous System response.

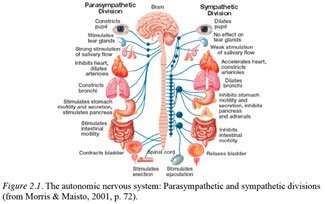

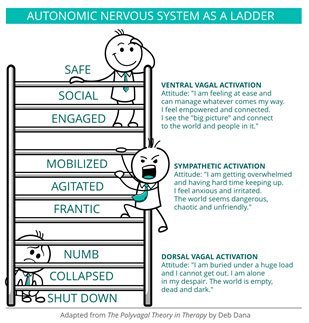

The Autonomic Nervous System Ladder below is a part of Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory. Porges found that the vagus nerve that moves through the torso up into our face connects our body and brain, sometimes called our gut-brain and our head-brain. It’s quite fascinating all the places we can influence our felt-sense of social safety through informed movement practices with sound and breath, specifically.

When we’re thriving, we’re in a Ventral Vagal activation state, our Upstairs Brain. For most people, when the threat of quarantine and illness first came, we jumped into Sympathetic Activation, sliding down into Downstairs Brain with fight-or-flight reactivity. No matter how many times we hear “We’re all in this together” there can still be an overriding sense of “There’s no way out” or “Nobody is looking out for me and there’s nothing I can do.”

That’s the Dorsal Vagal shut down response. We freeze when we don’t have the option to fight or flee. Think of a possum—pretending to be dead so that any predator would lose interest. We collapse when we truly feel “There is nothing I can do,” when we’ve lost all energy and belief in the ability to keep burning energy and resources: Usain Bolt caught and restrained, Jackie Chan all tied up, or Martin Luther King Jr. with glued lips after some time of trying to get loose. It too is a survival response—a conserving energy response.

If you’re experiencing a greater amount of exhaustion and nightmares, as many people are, chances are that fight-flight energy hasn’t had a way to get out and sunk down into an involuntary freeze or collapse Dorsal Vagal state. Nightmares occur when we have too much sympathetic activation. Deep REM sleep is the only time our bodies process information without the emotional charge of cortisol and adrenaline rushing the brain. Disney Pixar’s Inside Out has a pretty good representation of disturbed REM Cycle sleep in “Dream Productions.” Our brains attempt to make sense of any unprocessed material from the previous day through dreams. When life feels un-make-sense-able, our dreams are left chaotic and charged with fear.

Wake and sleep, our nervous systems are trying desperately to keep us safe and alive. In the process of making sense, we filter through what information will be stored for future retrieval and what will be discarded. Richard Miller offers two guided meditations on iRest.org for deeper rest that may be quite helpful for getting settled in your own nervous system as you lay down to sleep.

When we begin to move down the Ladder, we’re more jumpy, more reactive than reflective.

We’ve probably all been told to take a calm, deep breath. Sometimes even being told ‘calm down, take a breath’ can be unsettling.

When we inhale we tap the vagus nerve in our gut and as we continue to exhale, then inhale and repeat, key information is sent up into our brain saying: “You’re okay. You are going to be okay.”

There are so many methods of breathing. Below is a menu of soothing options. As you read through the practices, consider if it feels like a “Yes,” “Maybe,” or “No” for your nervous system. Goal: Try to slow down your breaths from 10-14 breaths per a minute to 5-7 breaths per a minute. All of the practices can be repeated until your heart rate feels calm to you, then repeat one more time noticing how it feels to feel calm.

In any practice, you’re growing awareness of what feels good or helpful to your nervous system, and, adding the Yes’ and Maybe’s to your toolbox. When we practice regularly, we build a habit of knowing the tool works. Then when something happens, we can rely on the tool to be there. If we don’t practice, when we flip our lid, we likely will forget there’s a toolbox all together.

With current circumstances intensifying the reality of uncertainty, I believe our primary responsibility is doing what we can—as individuals and as community—to protect and settle our own nervous systems and when we are settled lend our balance to another. Just as anxiety is contagious, calm is contagious too.

Our world is flooded with stress hormones right now. We’re actually in a collective trauma state. Trauma being a word used to express “life is too overwhelming for me to process and cope through with the tools I know.” When we are able to find some sense of calm, we have activated soothing hormones. We can then reach out to those whom we’re living with or through technology with others outside our places of shelter and share a sense of calm through eye contact or other gestures that increase our sense of connectedness hormones.

To do this, you can start by scanning how you’re spending your days. Where are you when you feel most activated? Who are you around? What are you doing? For example, I generally appreciate movies most when I cannot predict the ending. However, in the midst of global uncertainty, I’m choosing only to watch movies or television with my spouse, and all of our movies are predictable. If something begins to rush my system with stress or heightened anticipation, we choose together to turn the movie off. It’s one thing I can do to help my system feel a little more settled.

Just as we want to add helpful practices, we also need to scan our lives for habits or current behaviors that are adding to the noise and unsettledness of life. It’s about grieving what normal rituals and rhythm have been lost as Coronavirus came into the scene, and, finding the rhythm that best suites you and the people you love at this time.

Perhaps this commitment to building habits around taking responsibility to settle our own nervous systems and lend our settled systems to others more effectively can be our answer to the purpose of this suffering, as written about by Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning (1946). Will you imagine, with me, a more compassionate world filled with a greater sense of relational safety?

References

Brach, T. (2004). Radical acceptance: embracing your life with the heart of a Buddha. New York: Bantam Books.

Dana, D. (2020). “How to Help Our Nervous Systems During a Pandemic.” Psychotherapy Networker.

Kolacz, J., Kovacic, K. K., & Porges, S. W. (2019). Traumatic stress and the autonomic brain‐gut connection in development: Polyvagal Theory as an integrative framework for psychosocial and gastrointestinal pathology. Developmental Psychobiology. doi: 10.1002/dev.21852

Porges, S. W. (2011). Polyvagal theory: neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (2011). Mindsight: Transform your brain with the new science of kindness. London, England: Oneworld Publications.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2016). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your childs developing mind. Vancouver, B.C.: Langara College.